Between the days of compact cassettes and the arrival of the iPod, there was no ideal way of carrying your music around with you. Sure, the Sony Walkman was legendary in the portable music world, but cassettes were still a nuisance that would chew up if you so much as looked at them the wrong way.

Also, you couldn’t jump to the track you wanted to listen to and too much messing around would see you having to untangle the tape from the read heads in the player. Winding your tape back in with a cheap ballpoint pen was a common occurrence.

CDs were the main format by the early 90s, but portable CD players were pretty awful. Shock protection wasn’t really a thing in those early portable CD players, so you had to place them flat on a table and hope nobody with heavy feet walks by too quickly. Also, battery life was often atrocious. See, these were dark times.

However, Minidisc changed all that.

In around 1998 I picked up my first Minidisc player/recorder. It was an AIWA AM-F65 and it was a revelation.

Nearly CD quality, shock proof and with the ability to jump straight to the track you want. You could also delete tracks and replace them with others. I was hooked, recording disc after disc with the optical cable. Come the early 2000s and I’d have my first proper car too. Sure enough, I put a Kenwood (KMD-44) Minidisc head unit in there, so I could listen to all of those discs in the car too. A year later, Minidisc would appear in The Matrix. If it was good enough for Neo, it was probably good enough for me.

Whilst digital music was starting to appear in Ye Olde Internet, storage was still a problem outside of a 3.5″ desktop hard drive and connection speeds were glacial, with most of us rocking a 56kbit dial-up modem at the most. Portable devices with the ability to hold more than around 64MB of data were still to catch on. Heck, not even USB was all that well established and where it was, it was slow. Early music players like the iPod or Creative Jukebox shipped with a Parallel or Firewire connection along with USB1.

Minidisc used a form of compression called ATRAC to provide the same recording time as a CD, but in a much smaller package. It worked by removing sounds that were masked by other sounds –a process not too dissimilar to MP3, which we’ll be hearing about later. Best of all, you had to listen really carefully to notice any difference to the CD version.

Minidiscs were double sided and housed in a caddy, much like the old floppy disks we were (sadly) still using at the time –USB flash storage was still in its infancy too. The caddy meant they were surprisingly durable and ideal for listening on the move, or dropping down under your seat in the car, never to be seen again.

At the time, the best way to transfer music to Minidisc was using an optical (TOSLINK) cable, out of the back of a CD player. Once recorded, you could then edit the track names, so they would scroll by on the LCD screen and in-line remote. I’ll be honest, this part was really fiddly, but you got used to it after a while.

In 2001 the iPod would launch. Whilst it wasn’t the first mp3 player, its integration with the iTunes Store would prove too tempting a funnel for music listeners. By the mid 2000s it was pretty much all MP3, or Apple’s own AAC.

2001 was also the year Sony would release NetMD, sensing that it was about to be eaten alive by the MP3 players that were starting to appear. This would allow you to transfer your MP3s onto a disc and mess around with the track names using your computer, negating the need for a CD player, which was also on borrowed time.

Whilst Minidisc never really caught on in the US, it did to a certain extent in Europe, but still not to the degree that it did in Japan, where it would be a going concern up until the 2010s.

Sadly, the writing was on the wall out here in the west by the early 2000s and in 2003 I found myself with a Creative Nomad Jukebox 2 and didn’t really look back. A few more Creative players entered my collection, before an iPod Classic and then the iPhone 3G.

However, I’m feeling quite nostalgic at the moment. I’ve just acquired my first Minidisc player in over 20 years and…it’s strangely exciting. I picked up the Sony MD-N707, boxed with all accessories and a handful of blank discs for about £100 on eBay. It was in mint condition and I’ve just spent a few hours transferring a couple of my favourite albums onto the blank discs –Whitechapel’s ‘Kin’, Miles Davis’ ‘Kind of Blue’ and Paradise Lost’s ‘Draconian Times’.

Minidisc today

Whilst Sony shipped its last minidisc devices in 2013, TEAC and TASCAM continued making devices up until 2020. Blank minidiscs are also still fairly easy to get hold of, particularly Sony’s Niege range.

If you can find a device in good condition, you’ll likely get some good use out of it for years to come, particularly if it uses regular AA batteries. My MD-N707 uses a single rechargeable AA battery, which are still readily available.

You’ll need a source with an optical/TOSLINK output, or if you have a NetMD recorder, some software. This is where things get slightly thorny.

Way back when NetMD first appeared, Sony released its SonicStage software to support it, but that has long since been abandoned and is difficult to get running on Windows 10 or 11. Thankfully, an enterprising fellow named Stefano Brilli released a web application called Web Minidisc Pro that allows you to transfer music onto your NetMD device. You can access it through the ever-useful Minidisc Wiki.

Whilst it works… most of the time, it will occasionally fail without warning. However, I’ve successfully written a few discs now and all is good.

Thoughts

Whilst I’m as equally guilty as anyone for abandoning minidisc when the shiny new MP3s came along, I’m becoming acutely aware of what we’ve lost in these intervening years.

Back then, music devices had replaceable storage (Minidiscs, cassettes etc), replaceable batteries and were fairly easy to open up and replace parts when they wore out.

Nowadays, you’re likely to be listening to music from a streaming service that you will likely pay forever with nothing to show for it, whilst the artist also receives next to nothing for your investment, on a device with a battery and storage that has a finite lifespan, but cannot be easily replaced.

I have a sinking feeling that we need to turn back before we lose physical media and serviceable devices forever. I’m really glad people have taken to vinyl again. It’s not for me, I like CDs too much, but there’s a lot to be said for owning your favourite music in all its forms and formats.

As for minidisc, it is nice having a music player that doesn’t require an internet connection (I can still use TOSLINK); isn’t arbitrarily limited by the manufacturer’s firmware updates; and requires only single rechargeable AA battery to run.

If the end of the internet does come, at least I’ll still have something to listen to. My task for the coming days is to get the camera out again –my nostalgia collection has a few disc-shaped gaps in it.

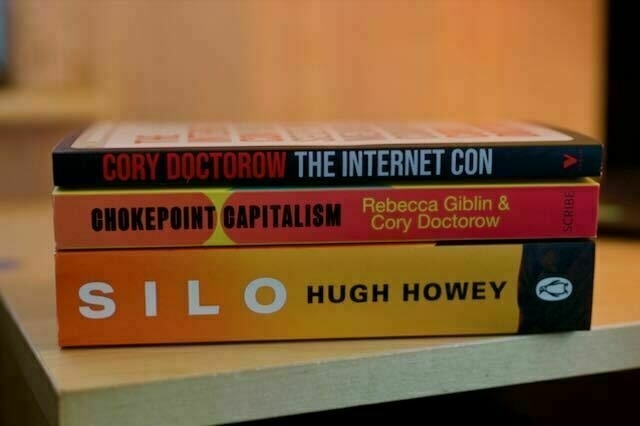

So, I bought some books recently. I didn't think about it much at the time of ordering, but these seem somewhat related.

So, I bought some books recently. I didn't think about it much at the time of ordering, but these seem somewhat related.